This turns out to be a fascinating subject, but one that I don't feel as though I know enough to write about. My audience (you folks) is probably too diverse to make assumptions about, but I'm guessing that some of you don't think twice about those really complicated highway interchanges that have ramps going in fifty different directions, with overpasses and bridges and underpasses, and the rest of you haven't seen anything more complicated than a cloverleaf!

I lived for years in rural parts, and when I went back to drive through Pittsburgh one time, I was amazed at the --seemingly unnecessary-- complicated highway interchanges I saw. I had, of course been familiar with cloverleafs, the simple design of a pair of highways crossing roughly at right angles. You had a plan whereby all you had to know to do was merge, and you were set for life. You took an exit, and if you wanted to turn right onto the other highway, you turned through 90 degrees, and merged back in, at another level, of course, because the other highway had to go either above yours, or below. So you turned through the 90 degree angle while you either climbed about 20 feet, or dropped about 20 feet.

To turn left, you also took an exit (on the other side of the intersecting highway, onto which you wanted to get), went through 270 degrees --three quarters of a full circle-- and either climbed or dropped the twenty-odd feet of difference in level, and merged into the slow lane of the other highway.

|

| Cloverleaf, with the left-turn circles outside the right-turn ramps. |

|

| Cloverleaf, with the circles inside the right-turn ramps. |

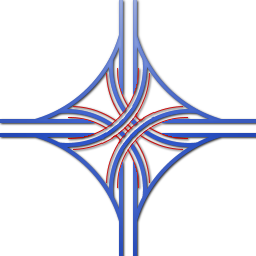

The problem with cloverleafs (cloverleaves?) is that the left-turning traffic has to go round this enormous circle. Furthermore, the cloverleaf does take up a lot of real estate. Another design that was invented in the sixties (or the late forties, if our Internet sources are to be trusted), is the stacked interchange. I just learned about them a few days ago, and I began to realize that they were things I had driven through, but they had looked so complicated I had seriously doubted I could ever understand them. It turns out that, well, they can be symmetric enough for anyone to understand, but they have lots of alternative configurations for highway engineers to make dozens of variations on the design.

The main idea is this. (See picture below.)

The two intersecting highways are separated vertically by about 100 feet. This alone is enough to boggle the mind, but the variations on the design might be a lot less high. Now, anyone in any of the roads turning right goes off a ramp, and joins the slow lane of the (other) highway in the usual way. (Since the two roads are at such different horizontal levels, the ramps involve some possibly steep climbs.) Suppose you're heading North, and now want to turn "left" to take a Westbound highway. You take the exit ramp with the Eastbound cars. Now the ramp splits, and you follow a link that drops you onto the on-ramp which the cars that had been on the Southbound highway (originally going in the opposite direction to you) have taken, who are now also going West. That's it. A ramp-to-ramp connecting link.

On the plus side, you don't have to go round that enormous circle. Also on the plus side, any high-rises that might have been situated near the intersection can continue to exist, except that now they have this enormous interchange that rises around 100 feet into the sky, right next to them!

The extra height is needed for the connecting ramp-to-ramp links I wrote about. There are altogether four connecting links, for all the traffic that wants to turn "left". Two of them can go side-by-side at the same level: for instance the Northbound-to-Westbound link, and the Southbound-to-Eastbound link. Two more can be at the same level, but different from the first pair: the Westbound-to-Southbound link, and the Eastbound-to-Northbound link. So four levels are required, which makes the intersection very high, and gives birth to the description stacked interchange.

| |

| Judge Harry Pregerson Interchange Interstate 105 and Interstate 110 |

This view of the Pregerson Interchange clearly shows the cloverleaf that replaces one of the links, in the bottom right of the photograph. Notice that, for the most part, the outer boundaries of the interchange are quarter-circles curving inward, so that the none of the buildings in the hollow of three of the curves needed to be removed, nor their parking lots. (God forbid we should steal a parking lot to make an interchange, right?)

The very oldest stacked interchange, reputedly, is the Bill Keene Memorial Arroyo-Seco Interchange in California which was completed in 1949, long before the vast majority of Americans were familiar with intersections between limited-access highways. It may have looked very different from its present day appearance, but according to at least one article in Wikipedia (which is where I have got every little bit of this information), this one was the first.

Note that though I say that the connecting ramps may lie at the same level in two pairs, the connecting ramps (which I also called links above) may very well slope throughout their lengths, since their ends are at different levels. (If the Arroyo Seco and the Harry Pregerson interchanges are the same, someone please let me know!!!)

Note that though I say that the connecting ramps may lie at the same level in two pairs, the connecting ramps (which I also called links above) may very well slope throughout their lengths, since their ends are at different levels. (If the Arroyo Seco and the Harry Pregerson interchanges are the same, someone please let me know!!!)This blogpost is about highway bridges and ramps that are very high above the lowest deck level, generally, as well as walkways that are high about road level. There are several images available on the Web showing such high-level walkways.

The set of walkways on the left is in the convention center in mid-town Atlanta, the walkway on the right connects buildings in Covent Garden, the well-know music, ballet, and opera center in Britain. The long passenger walkway in the middle is in Gatwick Airport in the UK, designed to allow planes to pass under it.

No comments:

Post a Comment